Patellar luxation is a condition where the knee cap does not run in its groove but slips off to the side. Luxation is a learned word for “slipping”. It is a condition which is regularly encountered in dogs and more commonly in toy breeds. The condition can be developmental or traumatic in origin.

Patellar luxation is a condition where the knee cap does not run in its groove but slips off to the side. Luxation is a learned word for “slipping”. It is a condition which is regularly encountered in dogs and more commonly in toy breeds. The condition can be developmental or traumatic in origin.

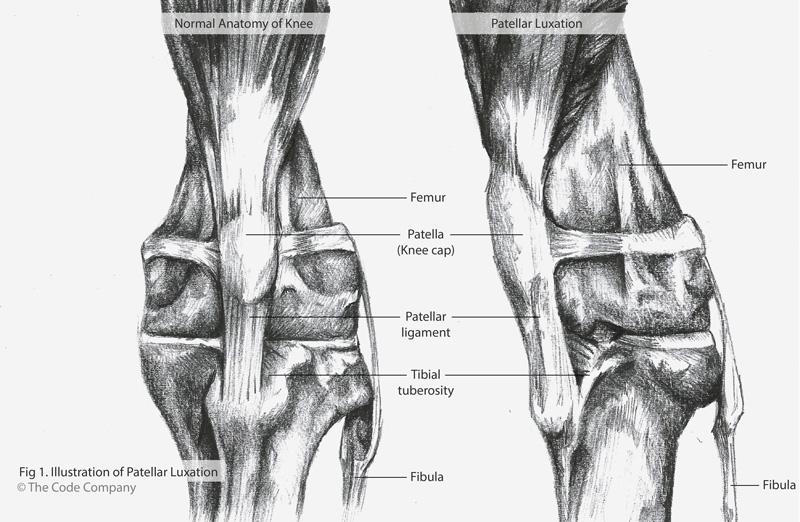

To understand the condition better, it helps to know what the anatomy of the knee looks like. The patella is commonly known as the knee cap and sits at the bottom of the big muscle group of the upper front part of the hind leg called the quadriceps. The patella makes up the front part of the knee and glides in the middle groove of the big bone of the upper part of the hind leg, the femur. This groove is known as the trochlear groove. The groove looks like a valley with two mountain ridges on either side. The ridges on either side of the groove are known as the trochlear ridges. The ridge on the inner part of the leg is known as the medial trochlear ridge and the one on the outer part is known as the lateral trochlear ridge. The knee cap or patella fits nicely in between these two ridges and glides up and down the groove as the knee bends. The patella is stabilised by the big muscle group to the top of it, the strong ligament to the bottom of it and the ligaments and connective tissue to the sides of it. The patella ligament which sits below the patella, implants onto the front of the top part of the bone underneath the femur, the tibia, also known as the shin bone.

Patellar luxation occurs when the patella slips out of the trochlear groove, usually when the leg is flexed or bent.

Medial Patellar Luxation

This is where the patella slides off towards the inside of the leg. It is more commonly seen in small breed dogs like Boston terriers, Yorkshire terriers, Chihuahuas, Pomeranians Miniature Poodles and Pekingese. The condition is also often seen bi-laterally, which means it affects both hind limbs.

Patellar luxation results in discomfort and reduced functional usage of the affected limb.

There are numerous reasons why this conditions occurs which are mostly related to anatomical problems like the groove in which the patella runs being too shallow, or the ridges on either side of the groove not going up high enough to prevent the patella from slipping over them, to the front top part of the shin bone not aligning well with the bottom part of the femur and instead of running in a nice straight line, the patella is continuously pulled off to one side as the leg moves backwards and forwards.

Because the anatomy is passed on from one generation to the next, it is not a good idea to breed with an animal affected by this condition.

Dogs who suffer from this condition have different symptoms. Some will show no symptoms whatsoever and a routine examination will show that the patellae are slipping off to the side whereas other dogs will be limping lame and will hardly be able to take any weight on the affected leg. Owners of affected dogs often complain that the patient carries the hind limb in the air for a few steps, and then shakes or straightens the leg, after which they can take weight on it again. Stretching of the leg aids in returning the patella into its normal position inside the trochlear groove, and once this is done the patient will be more comfortable and carry weight on the leg again.

A diagnosis is often made by the vet feeling up and down the knee and using the fingers to move the patella from side to side and attempt to slip the patella in and out of its groove. The relative anatomical positions of the big muscle group (the quadriceps), the trochlear groove, the patellar ligament and upper front part of the shin bone (the tibeal tuberosity) should also be assessed. Light sedation may be required to assess the integrity of the ligaments of the knee joint. X rays of the hips, knees and lower limbs will aid in diagnosing any other conformational abnormalities or bony changes. At least two X ray views are required to see the bones and joints from different angles.

Four grades of patellar luxation can be distinguished:

Grade 1: The patella can by hand be manipulated out of the trochlear groove but spontaneously returns. This grade shows minimal clinical signs.

Grade 2: There is spontaneous movement of the patella out of the trochlear groove but it can easily be replaced back into the groove by manipulation or by itself. This grade often goes hand in hand with symptoms described as a ‘skipping’ type lameness. The patella, when slipping out the groove, causes the dog to keep the leg in the air and when it slips back into the groove, the dog takes weight on the leg again. Over time, the cartilage surface underneath the patella and on top of the trochlea is damaged which allows progression to Grade three.

Grade 3: The patella is out of the trochlear groove permanently but can be manipulated back into position but usually slips back out of position as soon as the leg is bent or straightened. Bony deformities are usually present and there is inward rotation of the tibia. Usually a trained hand can feel that the trochlear groove is shallow.

Grade 4: The patella sits outside the trochlear groove permanently and cannot be manipulated back into the groove. Early surgical correction is critical to limit bony and ligamentous deformities which make surgery more challenging.

Damage to the cartilage may take place as the patella continues to slip in and out of the trochlear groove, exposing the bone and resulting in arthritis and pain. With the patella luxating, the cranial cruciate ligament, which is a ligament within the knee joint, is also placed under more strain due to the fact that the patella, if it sits in its normal position in front of the knee, provides stability for the joint. When the patella slips to the side it puts a lot more strain on the ligaments inside the knee and this can cause the ligament inside the knee to tear.

Grade one and two are recurrent luxations. With grade three and four, the patella is usually permanently luxated from the trochlear groove. Surgical correction is considered for grade two luxations when there are significant enough clinical signs to warrant it. In cases of grade three and four luxations surgery is recommended early on to limit damage to the bones and ligaments and progressive skeletal deformity and osteoarthritis. Surgical correction is often more challenging when cranial cruciate ligament disease or hip dysplasia is present.

There are several different strategies that are used singularly or in combination, to correct the luxating patella, and the technique used will depend on severity of the condition as well as the conformational abnormalities present. The surgeon will take all of this into consideration when choosing a particular technique.

- Soft tissues around the patella are reconstructed, so that the side to which the patella is slipping is loosened and the opposite side tightened

- Deepening the trochlear groove to enhance better positioning of the patella

- Moving the front, upper part of the shin bone so that the patella ligament runs in a straight line from the top rather than being pulled to the side.

Lateral Patellar Luxation

Lateral patellar luxation is more commonly seen in young large and giant breed dogs (Great Danes, St Bernards and Irish Wolfhounds). This is where the patella slips towards the outside of the leg.

The main cause of this condition is poor conformation most notably knock knees. Because it is related to the confirmation of the dog, both knees are usually affected at the same time. Intermittent luxation and reduction of the patella in the young and adult animal will result in progressive wearing of the outer trochlear ridge, a shallower trochlear groove and increased instability of the patella.

Clinical signs can be present from as early as 5 to 6 months of age. Physical examination of the knee joint is often diagnostic and the patella can be felt slipping to the outside of the leg (luxating laterally), but it is often reducible. Just as with a medially luxating patella the cranial cruciate ligament and ligaments to the side of the knee joint should also be assessed. Oftentimes there will be a laxity of the inner side ligament of the knee due to the chronic outer rotation of the limb at the knee joint. X rays are also required to assess potential damage, and/or deformities of the hips, the femurs and the shin bones, which are often more severe than with medial patellar luxation. Three dimensional Computed tomography (CT) may aid in planning where the shape of the femur or tibea needs to be surgically corrected.

The Grading system (1 to 4) for medial patellar luxations also applies for lateral patellar luxations.

Feeding ultra-premium diets with the correct calcium and phosphorus ratio, will aid in maintaining a slow growth rate, which has been proven to have a favourable effect in minimising hip dysplasia and other bone growth abnormalities, which could complicate and contribute to patellar luxation.

Surgery is the treatment of choice for lateral patellar luxation.

Post operatively

Over 90% of owners are satisfied with the progress of their dog after surgery.

For medial and lateral patellar luxations, soft padded bandages are used to aid in reducing the swelling post operatively. Removal of bandages after 3 to 5 days to allow full joint motion is encouraged. Pain medication is used as a matter of course.

Weight bearing post operatively is desired as soon as possible, as some toy breeds develop the habit of carrying the operated limb in the air. Swimming and hydrotherapy is a good way to encourage movement without having to take weight on the leg shortly after the operation. Restricted movement and leash walks are encouraged for the first 4 to 6 weeks (to promote adequate bone healing). No running and jumping is allowed. Depending on the size of the dog and the severity of the surgery required to correct the problem, dogs operated on one side should usually start taking weight on the affected leg within 10 to 14 days after surgery.

The prognosis for Grade one and two luxations is usually good. For grade three and four luxations the prognosis is fair to good, especially if the luxations were treated early in the patient’s life. Should the condition have been there for a long time with significant bony changes, the prognosis is more guarded. Secondary arthritic changes and cranial cruciate trauma could complicate long term function.

Osteoarthritis in the affected knee still progresses even after surgery regardless of the grade of luxation at presentation and therefore, depending on the degree, there may always be some degree of discomfort in the joint after surgery.

The prognosis for luxations in large breed dogs is less favourable especially when combined with angular deformities of long bones, or hip dysplasia.

Regular check-ups with the vet will ensure early detection and treatment to ensure your dog has the best chance of receiving the correct treatment and the best possible chance of recovery, should it suffer from patellar luxation.

© 2018 Vetwebsites – The Code Company Trading (Pty.) Ltd.